Software engineers worth their salt are always searching for ways to improve their code quality. Fortunately for them, there’s a reliable way to evaluate the health of a codebase and project, and that’s through the use of metrics. Today’s post is all about a specific metric. You’ll learn how to reduce cyclomatic complexity and, more importantly, why you would want to do it.

We’ll start by defining cyclomatic complexity. After that, you’ll learn why having cyclomatic complexity too high is a problem and why you would need to reduce it.

After the “what” and “why,” we’ll finally get to the “how.” We’ll show you tactics you can adopt to reduce the cyclomatic complexity of your code. Let’s get to it.

Cyclomatic complexity refers to the number of possible execution paths inside a given piece of code—for instance, a function. The more decision structures you use, the more possible branches there are for your code.

Cyclomatic complexity is especially important when it comes to testing. By calculating the cyclomatic complexity of a function you know the minimum number of test cases you’ll need to achieve full branch coverage of that function. So, we can say that cyclomatic complexity can be a predictor of how hard it is to test a given piece of code.

Confused? Understanding cyclomatic complexity doesn’t have to be complex.

Cyclomatic complexity is the minimum number of test cases needed to achieve full branch coverage. So cyclomatic complexity can predict how hard it is to test a given piece of code.

Consider the following function written in pseudocode:

Since it has a single statement, it’s easy to see its cyclomatic complexity is 1.

Now, let’s change things a little bit:

void sayHello(name, sayGoodbye = false)

The second version of the function has a branch in it. The caller to the function might pass true as the value for the sayGoodbye parameter, even though the default value is false. If that does happen, the function will print a goodbye message after saying hello. On the other hand, if the caller doesn’t supply a value for the parameter or chooses false, the goodbye message won’t be displayed.

So, the function has two possible execution branches, which is the same as saying that it has a cyclomatic complexity value of 2.

Cyclomatic complexity isn’t intrinsically bad. For instance, you can have a piece of code with a somewhat high cyclomatic complex value that’s super easy to read and understand.

However, generally speaking, we can say that having a too high cyclomatic complexity is either a symptom of problems with the codebase or a potential cause of future problems. Let’s cover some of the reasons why you’d want to reduce it in more detail.

Cognitive complexity refers to how difficult it is to understand a given piece of code. Though that’s not always the case, cyclomatic complexity can be one of the factors driving up cognitive complexity. The higher the cognitive complexity of a piece of code, the harder it is to navigate and maintain.

As we’ve already mentioned, higher values of cyclomatic complexity result in the need for a higher number of test cases to comprehensively test a block of code—e.g., a function. So, if you want to make your life easier when writing tests, you probably want to reduce the cyclomatic complexity of your code.

You’re likelier to introduce defects to an area of the codebase that you change a lot than to one you rarely touch. In addition, the more complex a given piece of code is, the more likely you are to misunderstand it and introduce a defect to it.

So, complex code that suffers a lot of churn—frequent changes by the team—represents more risk of defects. By reducing the cyclomatic complexity—and, ideally, the code churn as well—you’ll be mitigating those risks.

We’ll now go over a few practical tips you can use to ensure the cyclomatic complexity of your code is as low as possible.

All else being equal, smaller functions are easier to read and understand. They’re also less likely to contain bugs by virtue of their length.

If you don’t have too many lines of code, you don’t have lots of opportunities for buggy code. The same reasoning applies for cyclomatic complexity. You’re less likely to have complex code if you have less code period. So, the advice here is to prefer smaller functions.

For each function, identify their core responsibility. Extract what’s left to their own functions and modules. Doing that also makes it easier to reuse code, which is a point we’ll revisit soon.

Flag arguments are boolean parameters you add to a function. People usually use them when they need to change how a function works while at the same time preserving the old behavior.

What to use instead of flag parameters? In a nutshell, you can use strategies that accomplish the same result without incurring high complexity. For instance, you could create a new function, maintaining the old one as it is and extracting the common parts into its own private function.

If the flag parameter is being used to enhance or improve the behavior of the original function somehow, you might want to leverage the decorator pattern to reach the same end.

You might consider this one a no-brainer. If the decision structures—especially if-else and switch case—are what cause more branches in the code, it stands to reason that you should reduce them if you want to keep cyclomatic complexity at bay.

Some of the tactics we’ve just seen can contribute to reducing the number of if statements in your code. For instance, instead of using flag arguments and then using an if statement to check, you can use the decorator pattern.

Instead of using a switch case to go over many possibilities and decide which one the code will execute, you can leverage the strategy pattern. Sure, at some point in the code, you’ll still need a switch case. After all, someone has to decide which actual implementation to use. However, that point becomes the only point in the code that needs that decision structure.

Sometimes, you have functions/methods that do almost the same thing. Keeping both increases the total cyclomatic complexity of your class or module. If you can limit your duplicates, you can limit complexity.

Remove duplicated code by:

There are many reasons why it’s a good idea to remove obsolete—i.e., dead—code from your application. For our context, it suffices to say that that’s a “free” way to bring code coverage up and cyclomatic complexity down.

Just use a tool that lets you identify dead code—even your IDE might be able to do it—and then delete it mercilessly.

Let the developer who never wrote a function—or even a couple of them—to perform date formatting cast the first stone! It’s almost like a rite of passage.

Writing code that simply duplicates functionality that your language’s standard library or your framework already provides is a sure way to increase complexity unnecessarily. If code is a liability, you want to write only the strictly necessary amount of it.

Implement a sound code review strategy that’s able to identify and get rid of such wheel reinventions.

Cyclomatic complexity is one of the most valuable metrics in software engineering. It has important implications for software quality and maintainability, not to mention testing.

High cyclomatic complexity might be both a signal of existing problems and a predictor of future ones. So, keeping the value of this metric under control is certainly something you want to do if you want to achieve a healthy codebase. Keeping it under control is exactly what you’ve learned with our post.

Before parting ways, a final caveat. Keep in mind that no metric is a panacea when used in isolation.

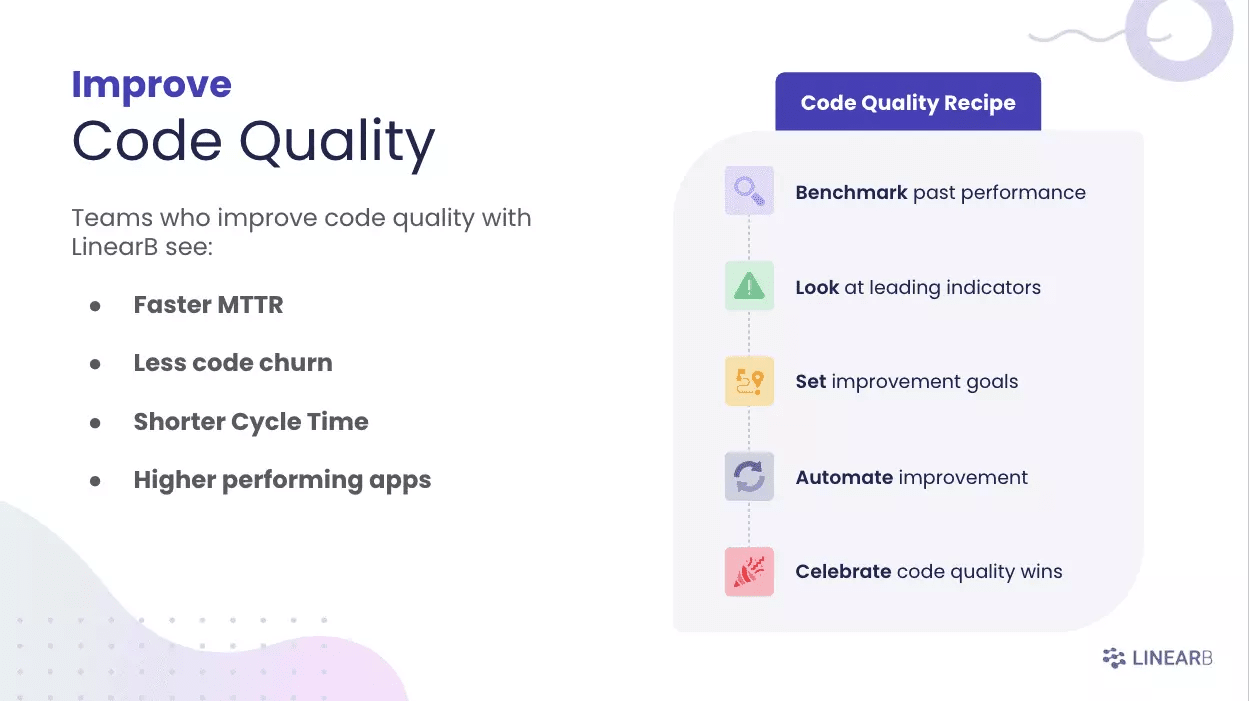

Often, what you’d really want to do is to track and improve a group of metrics that, together, can give you the big picture view of the health of your team and project. The best way to do that? Get a demo of LinearB.

LinearB is here to help you spot where there might be problems in your process. If you’d like to learn more and improve your own code quality, check out our five-step recipe for improvement.